“Back again on the cattle-cars we went. This time more prepared for what to expect. At least we knew that this time there wouldn’t be any machine-gun fire to dodge. Just hunger. We were always trying to dodge hunger. My brother and I would quickly leap from the train to steal radishes and carrots from gardens we would pass, against Mutti’s wishes. I didn’t understand the difference at the time between stealing from a farm-field and stealing from a personal garden, but Mutti did and scolded us for this. Sometimes we’d hop out and play on the tracks. waiting for military trains to pass. We’d stop frequently as we had to wait for passing trains, and on one of those stops Mutti remembered that her brother’s in-laws lived in the town we had stopped at. She was permitted to leave the train for a few hours as we waited. We had to stay with the officials in charge of the refugees.

Soon, Mutti returned with a huge smile on her face. “Get the luggage! Get your backpacks! We’re staying in Minden!” She beamed with happiness, as she hugged and kissed us. She had found us a place to stay! Mutti had not known where her brother’s in-laws lived, but she knew their last name, so she had asked the conductor if he had known anyone by the name of Busche who had retired from the railway. As luck would have it, he knew the street Mr. Busche had lived on. So Mutti, went door to door knocking at each house, hoping that her relatives would open the door.

The streets at this time were filled with homeless people and refugees. Many people from Eastern countries like Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. Many who didn’t speak German. Many people were dirty and ragged, and after days on the train, we looked nearly as rough. Miraculously she found their home, and after explaining our situation, they offered us a place to stay.

Days before our arrival, Minden had passed the “Refugee Resettlement Act”, that required that all households open their homes to refugees if they had more than one room per person. The Busche’s owned a home with a five rooms, and they were being forced to give up three of their rooms to strangers. Scared of who might be made to move in, Mutti showing up on their door was a perfect solution.

We would be the refugees that they had move into their home! We were no longer homeless!

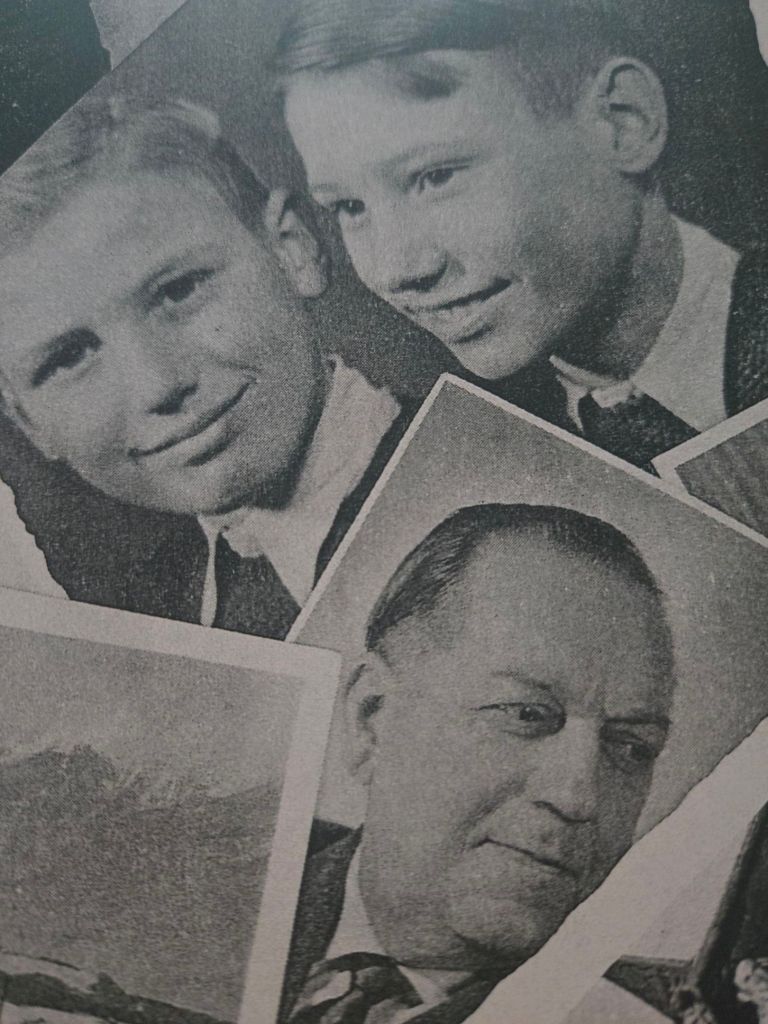

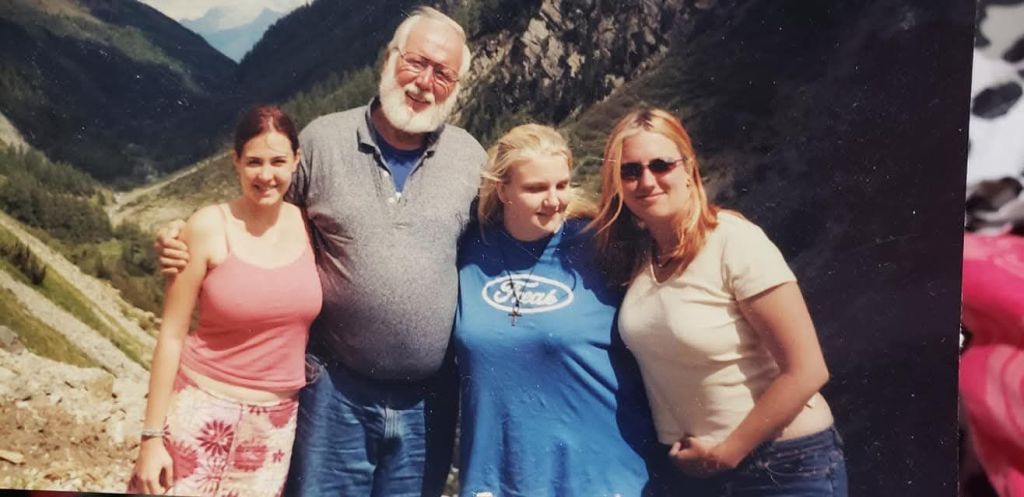

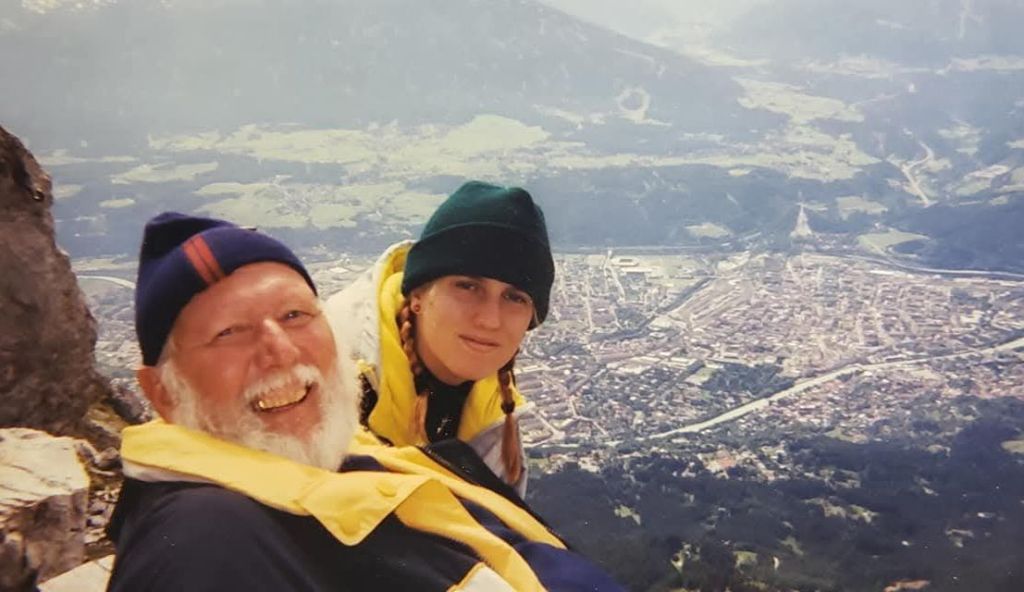

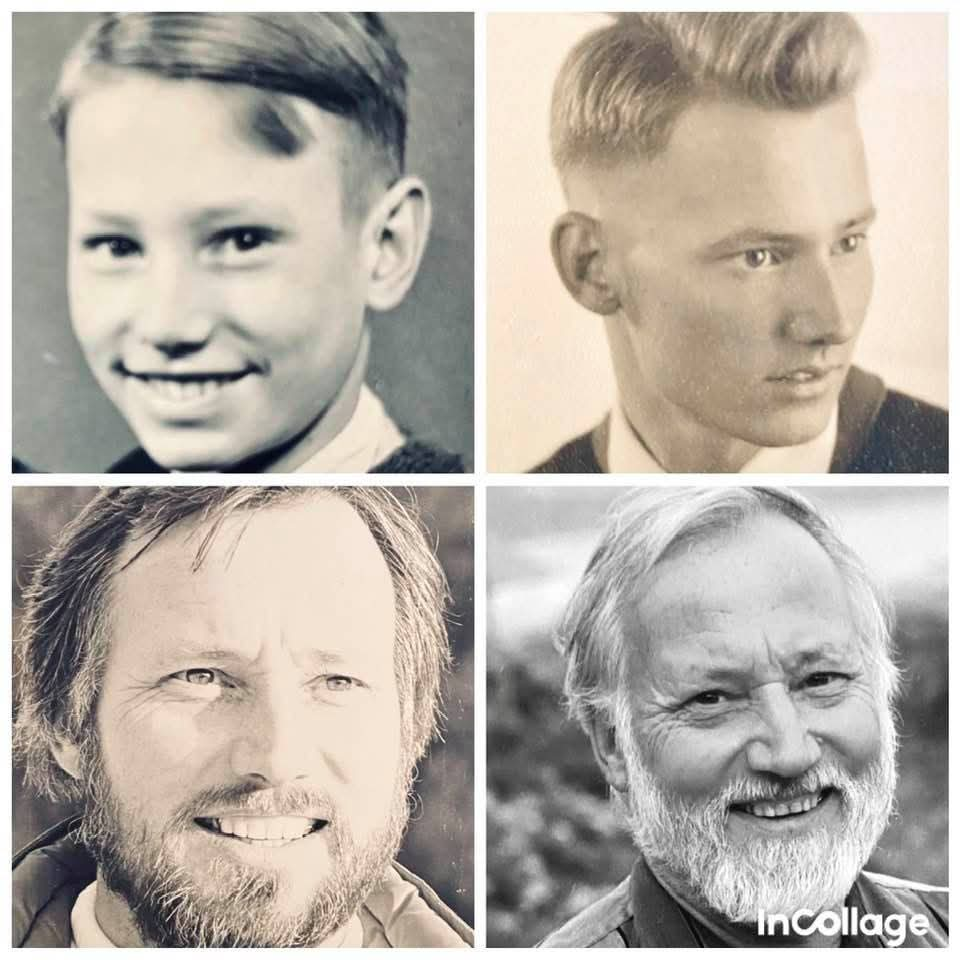

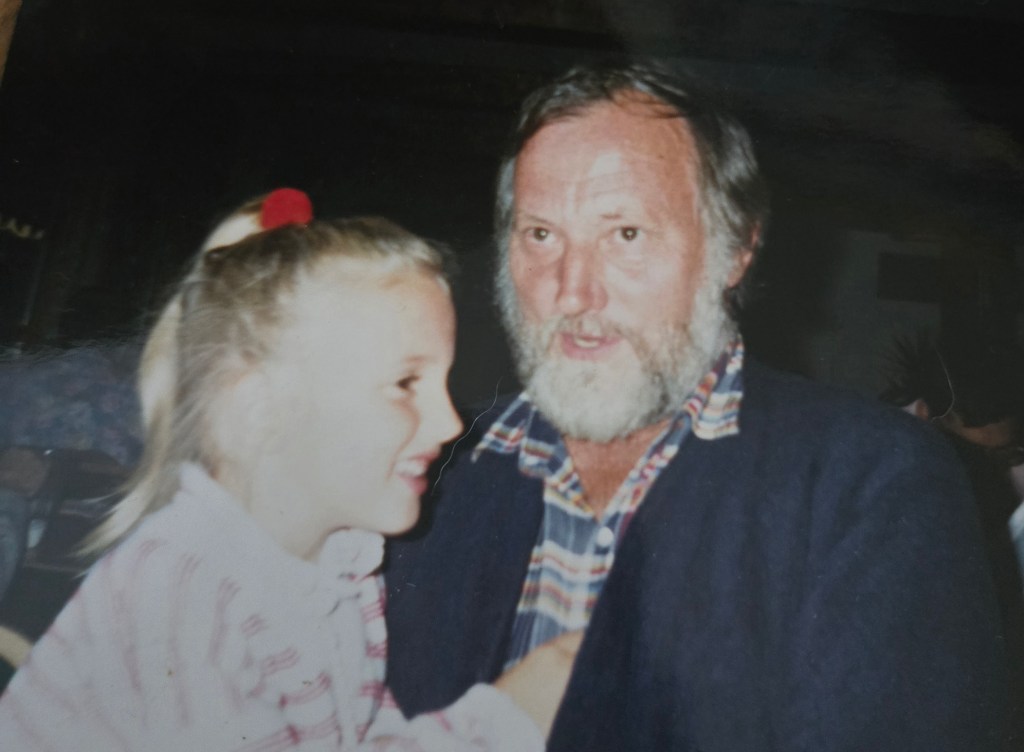

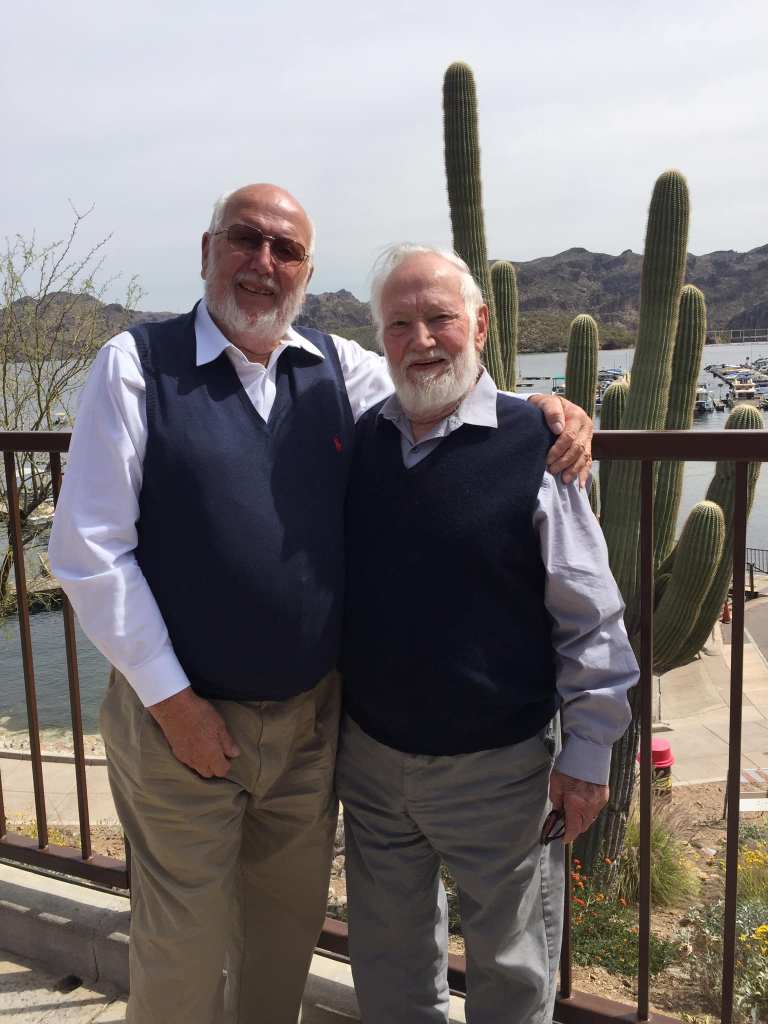

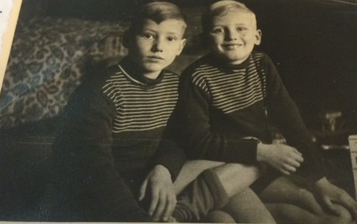

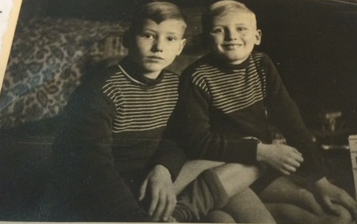

Opa and Omi Busche were incredibly welcoming. We had never met them, but they made us feel at home and shared whatever we needed with us. In no time, Mutti had found a job as a Masseuse at the local hospital. While she worked, Opa watched over us and taught us many things. Opa was a retired railroad man, but now his main hobby was gardening. This was a wonderful hobby to have at the time, since food was so scarce and hard to find. He had a cellar packed full of root vegetables that he had grown and stored, which kept us from starving, when others had nothing. He also fed the others in the nearby apartments as much as he could during this time of famine and starvation. When we were home, Opa kept us busy in the garden. He taught us how to build raised beds and weed and plant and harvest. We were even allowed our own small garden where I planted radishes, carrots, and beets, while Gottfried planted flowers and potatoes. These useful skills I still remember to this day. This was our education while we still were not back in school due to the war disruptions.

Since there was no school, children were to help with the procurement of food. I got my first job at a little bakery, where we would bake the strange corn flour the Americans provided, and attempt to make German breads, which turned out nearly inedible and hard. Some days we worked in the farm fields all day, just for the privilege of harvesting a single carrot or a few potatoes at the end of the day as our payments. Mutti traded her massages for food instead of money.

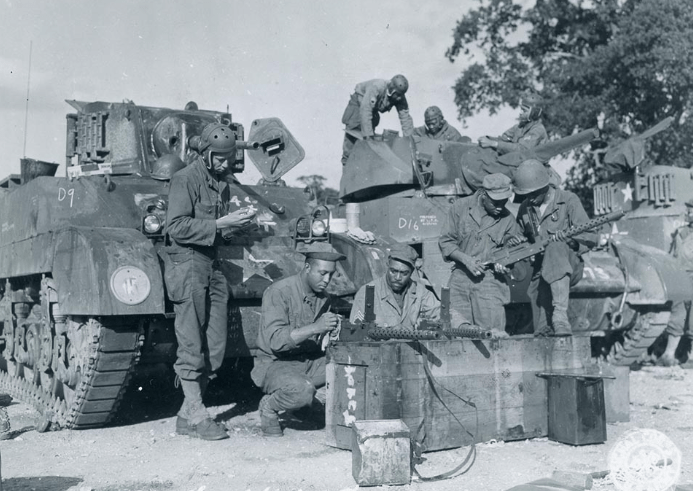

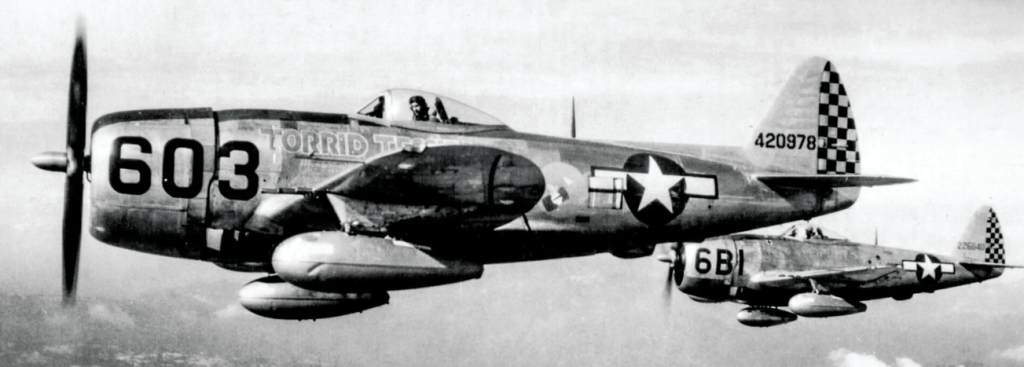

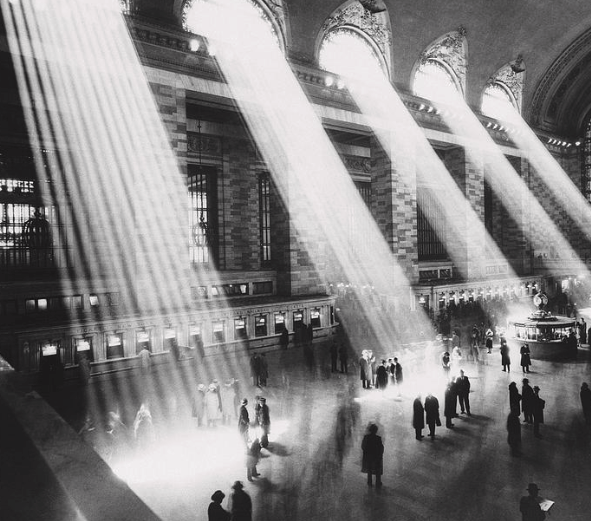

There was a nearby railway station, where a military field kitchen had been set up for the passing troop trains to come and eat. Gottfried and I would often go to the railroad to beg for food from the passing soldiers. Whenever a train would pass, we would jump and shout and beg.

“DONUTS!!” This was the first word that I mastered in the English Language. We were always hoping for American troop trains, because soldiers would throw us donuts or once in a while a candy bar.

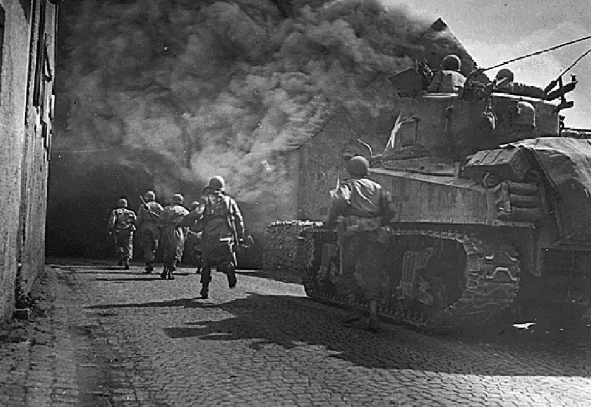

After the war, hunger was rampant. It seemed everyone was starving, and on the outskirts of Minden stood a number of gigantic silos and the storage magazine. What used to be a major food supply center, was now graded by British soldiers. There was still a lot of food inside, and one day there was a revolt of the starving population of Minden. A mass of people stormed the depot.

Despite warning shots, everyone ran to grab whatever they could. Since Gottfried and I were nearby, we joined the crowd. In the warehouse, we found a 5 gallon tin-can of molasses. We each took one handle, and struggled to get it home as it swung back and forth between the two of us rushing to get it back in the house. Opa hid this in the cellar, just in-case someone came looking for the stolen goods.

You had to do what you could to survive those days. And we were proud we had helped feed our family.” – Jochen

It’s hard not to make comparisons while writing my father’s story, to what is happening in the world today. The dirty part of war that is rarely discussed. What happens after, when populations are left with nothing and no way to get more. Homeless, lost, hungry, dying. Trying to survive in the rubble of what is left. My father and his family were so fortunate to find a loving home to lay their heads with a person who taught them skills to grow their own food, when no one had the money to buy food even if it was available.

Unfortunately, you can turn on the news and see every day, starving people in Gaza desperately begging for food which is being distributed by the Israeli military. I can’t help but make comparisons between the revolt in Minden, where people stormed the depot for food, and the scenes I’ve seen in Gaza where desperate people are rushing the distributions sites for food.

Unfortunately, there are more than just warning shots in Gaza. Every day people are being killed. Kids too. Starving kids being killed trying to get a bag of rice or whatever it may be. My heart breaks. Children starving to death, being gunned down. What is happening in the world today? I see the footage of people running with giant boxes or bags, and think of my Dad and Uncle Gottfried awkwardly running home with their stolen molasses.

Have we not learned lessons? Do only kids on one side of a war matter if they starve to death? My father was a German child, the losers of the war, so is what happened to him similar to what is happening in Gaza in regards to the famine and starvation? Thankfully, my father and Uncle made it home safe. Not everyone today is so lucky.

Just things I think about that are hard to ignore.

Maybe it’s in my blood now, but I’ve been gardening too recently. Working on growing food from seed. It’s such an important skill that I think is often lost by many. Maybe more people should learn. Have a “just in case” garden, where you can grow and enjoy and be slightly less dependent on grocery stores. So much is going on in the world today, and it can be a lot to handle mentally. Might I suggest getting your hands dirty? Reconnect with nature. Remember the ways of our ancestors.

Live! Love! Learn! Grow!

-Verina